Market Overview: Scale and Key Sectors

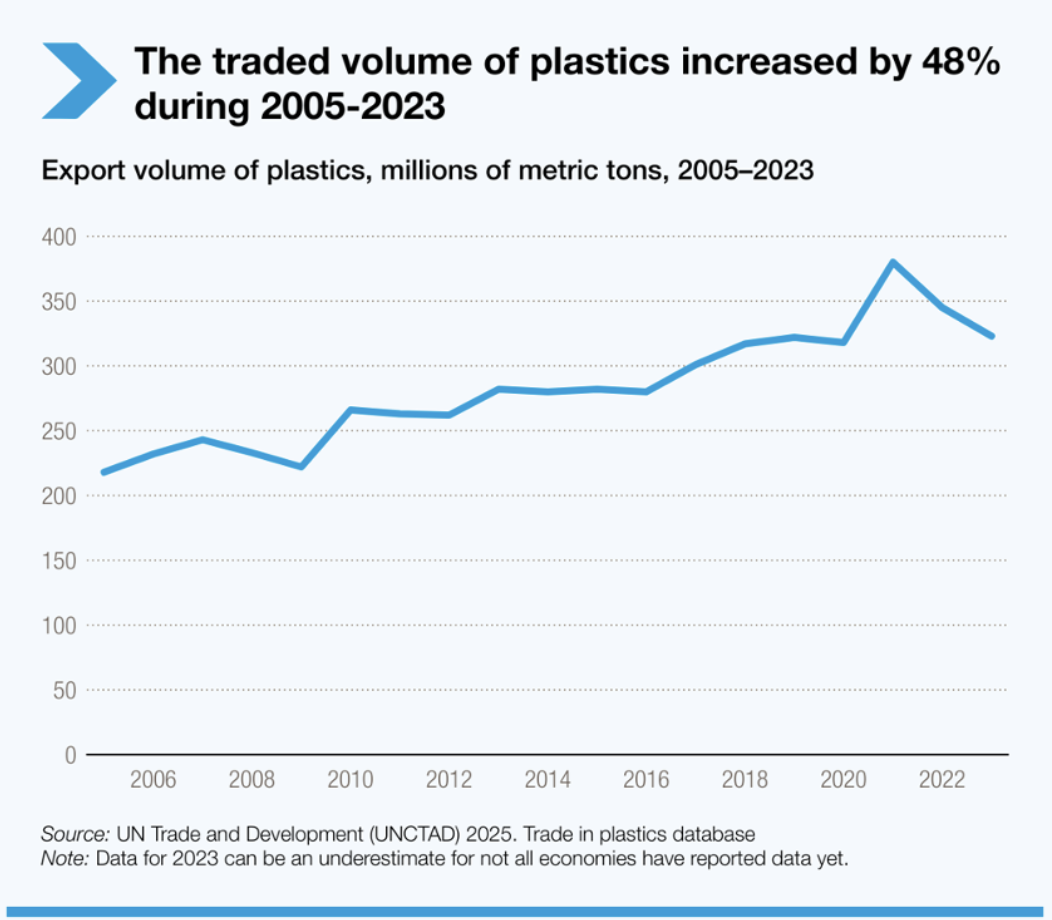

Plastic has become a cornerstone of the modern economy – from packaging and consumer goods to construction and automotive parts. Global plastic production reached approximately 436 million metric tons in 2023, a figure that has climbed steadily over the past decades[1]. Packaging is the single largest use sector, accounting for about 36% of all plastics produced (mostly in single-use packaging)[2]. Other major uses include construction materials, textiles (synthetic fibers), consumer products, and automotive components. This huge production volume is mirrored by an equally massive waste generation each year, indicating a largely linear “take-make-dispose” model still dominates the plastics market.

Despite plastics’ economic importance and utility, a striking share are used in short-lived applications and quickly become waste. Out of ~430 million tons produced annually, about two-thirds are products with a short useful life that soon end up as waste[3][4]. According to the United Nations, roughly 280–360 million tons of plastic waste are generated each year[4][5]. In fact, packaging alone (much of it single-use) makes up about half of the global plastic waste stream[5]. Table 1 summarizes key global metrics illustrating the scale of the plastics market and its waste footprint:

Notably, plastics demand has historically grown faster than the global population. Between 2000 and 2020, annual plastics production nearly doubled (from ~234 million to 435 million tons)[9]. Without significant interventions, this growth is projected to continue: by 2040, production, use, and waste could increase by ~70% above 2020 levels under business-as-usual scenarios[10]. In other words, we could be producing on the order of 750 million tons of plastics per year by 2040 if current trends persist[10]. Such growth would outpace even population and economic growth, driven by rising consumption in developing markets and continued demand in developed ones. For instance, petrochemical companies are investing heavily in new production capacity – anticipating that plastics and petrochemicals will account for a large share of future oil demand growth. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that plastics will comprise nearly half of the growth in oil demand by 2050, as traditional fuel use plateaus [11]. This dynamic puts the plastics market at the crux of a broader energy transition: as transportation electrifies and overall oil demand slows, oil and gas companies see plastics as a key outlet for their products.

In summary, the global plastics market today is enormous and still expanding. It delivers valuable products across industries but also generates vast waste streams and environmental externalities. This reality has set the stage for intense scrutiny from governments, society, and investors, all of whom are increasingly pushing for a more sustainable and circular approach to plastics.

The Plastic Waste & Pollution Crisis

The flip side of booming plastic production is a mounting waste and pollution crisis. Of all the plastic ever produced (an estimated 8.3 billion tons since the 1950s), 75% has already become waste – much of it accumulating in landfills or leaking into the environment[1]. Unlike natural materials, most plastics do not biodegrade; they persist for decades or centuries. As a result, we now find plastic debris ubiquitous in oceans, soils, and even the air. An oft-cited projection warns that by 2050, there could be more plastic than fish (by weight) in the oceans if current trends continue. While exact outcomes are hard to predict, it is clear that plastic pollution poses a systemic threat to marine ecosystems, terrestrial wildlife, and potentially human health (via microplastics in food and water).

Every year, millions of tons of plastic waste “leak” into oceans. This includes everything from single-use packaging and bags to lost fishing gear. Once in the environment, plastic breaks down into microplastics that have been found in marine organisms at all levels of the food chain – and even in human blood and lungs in recent studies. The environmental damages are extensive: plastics entangle and harm wildlife, introduce invasive species via floating debris, and can adsorb and transport other pollutants. In addition, open burning of plastic waste (common in areas without proper waste disposal) releases toxic emissions.

A major factor is that waste management and recycling infrastructure has not kept pace with plastic production. According to the Alliance to End Plastic Waste, as of 2023 an estimated 70% of plastic waste is either uncollected, mismanaged (littered or dumped), landfilled, or openly burned – only about 30% is formally collected and treated in any way[12][5]. Global recycling rates for plastic remain in the single digits to low teens. In 2021, only ~10% of plastic waste was recycled worldwide[6]. Around 50% was landfilled and the rest (~40%) was either incinerated or lost to the environment[6]. This means the world currently recycles just a tiny fraction of plastics, with the vast majority ending up as pollution or in disposal sites.

Importantly, there are stark regional differences in waste outcomes. Europe leads with about a 15% recycling rate for plastic waste (2019–2021 data) – higher than the global average but still low[6]. Asia’s recycling rate is around 12%, and North America’s is only about 5%[6]. (The United States in particular lags on plastic recycling; recent estimates put U.S. plastic recycling at 5–6%, due in part to the collapse of exported waste markets and challenges in domestic recycling capacity[6].) These low recycling rates reflect technical and economic difficulties in recycling many plastic types, as well as insufficient collection systems, especially in low-income countries. Developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America often struggle with waste management resources, leading to high rates of litter and open dumping. Indeed, mismanaged plastic waste is heavily concentrated in regions that lack formal waste infrastructure – a global equity issue since these regions often bear the worst pollution impacts.

The plastic pollution crisis also has significant economic and social costs. Coastal communities face cleanup burdens; tourism and fisheries suffer losses from polluted environments; and flooding can be exacerbated when plastic trash clogs drainage. Moreover, there are emerging concerns about human health: microplastics have been found in drinking water, table salt, and even the human bloodstream. Certain chemicals in plastics (like additives, plasticizers) can leach out and potentially impact hormone systems or cause other health effects. While research is ongoing, the precautionary principle is gaining ground to curb unnecessary plastic use and exposure.

Finally, the climate change connection bears mentioning. Plastic is fundamentally made of fossil hydrocarbons – roughly 98% of plastics are derived from oil or natural gas feedstocks[7]. Manufacturing plastic is energy-intensive, and when plastic waste is incinerated, it directly releases carbon dioxide. The UNEP estimates that in 2019, the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions from plastics were about 1.8 Gt CO₂e, or 3.4% of global emissions[13]. If current growth continues, plastics-related emissions could double by mid-century, consuming a larger share of the remaining carbon budget. In fact, by one analysis, petrochemicals and plastics could account for nearly half of the growth in oil demand by 2050 – outpacing sectors like aviation and shipping[11]. This means tackling plastic waste is not only an environmental imperative but also part of climate action. A circular plastics economy (more recycling, less virgin production) would avoid significant emissions.

In summary, the plastics market’s traditional linear model has produced a waste crisis with multifaceted impacts – ecological, economic, and climatic. This has not gone unnoticed: a wave of public awareness and activism has put plastics under the spotlight, leading to calls for stronger regulation and systemic change. Next, we examine how governments and industry are responding.

Regulatory Drivers and Global Policy Trends

In response to the plastic pollution challenge, policy and regulatory efforts are accelerating worldwide. Governments at all levels – local, national, and international – are introducing measures to curb problematic plastic uses and hold producers more accountable for end-of-life impacts. The regulatory landscape, however, is complex and still evolving, with different regions moving at different paces. This section outlines the key regulatory trends shaping the plastics market globally, including international treaties, national laws (like Extended Producer Responsibility schemes), and local bans or standards.

Global policy responses to plastic pollution are evolving. The timeline above highlights major international milestones – from the 1988 MARPOL treaty banning plastic dumping at sea, to the 2019 Basel Convention amendment treating plastic waste as hazardous, to the ongoing UN negotiations (2022–2025) for a comprehensive plastics treaty[14].

- International initiatives: At the highest level, the United Nations is in the process of negotiating a landmark global treaty on plastic pollution. In March 2022, 175 UN member states endorsed a resolution (UNEA 5/14) to develop a legally binding instrument covering the full life-cycle of plastics, from production to disposal[14]. An Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) has been convened, aiming to finalize the treaty by the end of 2024 or early 2025[15][14]. If successful, this agreement could impose coordinated rules on plastic production, design standards (e.g. toxicity and recyclability), waste management, and possibly reduction targets on a global scale. Observers compare its potential impact to the Paris Agreement for climate – in this case addressing plastic pollution with an international framework. As of mid-2025, negotiations are ongoing (INC-5 sessions), with key issues including whether to set limits on virgin plastic production, how to fund waste management in developing countries, and controls on hazardous additives[14][16]. While the treaty is under development, existing international law has seen some progress: for example, the Basel Convention was amended in 2019 to put stricter controls on transboundary movement of plastic waste[17]. This makes it harder for countries to simply ship plastic scrap to poorer nations without oversight. Additionally, trade policies are being examined – UNCTAD has highlighted that current trade tariffs favor virgin plastic over alternatives (tariffs on plastic goods have dropped to ~7%, while natural substitutes like paper or bamboo face higher tariffs ~14%)[18]. Aligning trade rules with plastic reduction goals is another frontier (e.g. potentially reducing tariffs on recycled plastic or substitute materials). In short, the global policy momentum is building, though a comprehensive treaty is still in the works and not yet in force[19].

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): One of the most significant regulatory trends at the national/regional level is the adoption of Extended Producer Responsibility schemes for plastic packaging. EPR shifts the burden of post-consumer waste management partly onto producers (manufacturers, brand owners, retailers) rather than just municipalities or consumers. In practice, EPR laws require companies to finance and/or organize the collection, recycling, or proper disposal of the packaging they put on the market[20]. This often involves paying fees to a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO) or government fund, proportional to the amount and type of packaging. Crucially, EPR fees are increasingly “modulated” by material type and recyclability – meaning plastic packaging, especially hard-to-recycle plastics, incur higher fees, whereas easily recyclable materials like aluminum or cardboard have lower fees[21]. This creates a financial incentive for companies to use packaging that is recyclable and to minimize difficult-to-recycle plastics (or pay the price for them). For example, in many European EPR programs, a ton of plastic packaging might carry a fee several times higher than a ton of paper or metal[21]. EPR is seen by policymakers as a way to internalize the environmental costs of packaging and spur eco-design.

Europe has been at the forefront of EPR and plastic regulation. The EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive (PPWD) mandates that all member states implement EPR for packaging by end of 2024[20]. As a result, nearly every EU country now has an operational EPR program covering plastics; these typically oblige producers to meet recycling targets and pay fees per ton of packaging placed on the market. The EU also set ambitious plastic recycling targets – for instance, aiming to recycle 50% of plastic packaging waste by 2025 and 55% by 2030 (up from roughly 40% today). In 2019, the EU passed the Single-Use Plastics Directive, which bans certain disposable plastic items (like straws, cutlery, cotton swabs, balloon sticks) and imposes measures on others (e.g. requiring member states to cut consumption of plastic food containers and cups, and ensuring manufacturers cover the costs of cleaning up litter from products like cigarette filters and fishing gear). Furthermore, the EU is moving toward mandatory recycled content requirements – for example, beverage bottles must contain at least 25% recycled plastic by 2025 (for PET bottles) and 30% by 2030. A new proposed regulation (Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation) is in the works, which could set binding targets for reuse/refill systems and further restrict excessive packaging. Europe’s approach is relatively uniform and strict, reflecting strong public support for action on plastics[22]. European regulators also introduced measures like a plastic packaging levy (€0.80 per kilogram of unrecycled plastic packaging waste, paid by member states into the EU budget) to incentivize improvements. The EU’s stance has effectively made it a global reference point – multinational companies must adapt their products to meet EU rules, and many other countries are watching these policies closely.

- North America (United States & Canada) has historically lagged Europe in national plastic legislation, but momentum is picking up at state and provincial levels. The United States does not yet have a federal EPR or plastic reduction law for packaging, and approaches remain fragmented (state-level)[22]. However, several states have forged ahead with EPR for packaging in the past few years. For instance, California’s Plastic Pollution Prevention Act (SB 54), passed in 2022, is one of the most sweeping U.S. laws: it mandates that 100% of packaging in California be recyclable or compostable by 2032, a 25% reduction in single-use plastic packaging by 2032, and a 65% recycling rate for plastic packaging by 2032[23][24]. California’s law essentially creates an EPR program where producers must join a producer responsibility organization and pay for recycling and waste reduction, with enforceable targets. States like Maine, Oregon, Colorado, and Washington have also enacted EPR laws for packaging, each with their own nuances (fee structures, covered materials, etc.). Besides EPR, many U.S. states and cities have implemented bans or fees on specific items – e.g. plastic grocery bag bans in numerous cities and states, bans on polystyrene foam food containers in others, and plastic straw upon-request laws. While there is no unified national policy, these sub-national regulations are creating a patchwork that companies must navigate. Canada, for its part, has announced a national ban on certain single-use plastics (bags, straws, stir sticks, six-pack rings, cutlery, and hard-to-recycle takeout containers), which began rolling out in 2023. Canada is also moving toward EPR for packaging at the provincial level (provinces like Ontario and Québec have programs to make producers fund recycling). In short, North America’s regulation is catching up in the form of state/provincial initiatives and specific product bans, even as comprehensive federal action remains to be seen.

How can rePurpose Global’s platform help navigate plastic and packaging regulations?

The Packaging Compliance Platform helps:

- Translate SKU-level packaging data into specific EPR obligations by region.

- Forecast future compliance costs under multiple scenarios.

- Recommend design interventions to lower fees and improve recyclability.

- Generate audit-ready reports aligned with EU, U.S., and Canadian regulations.

This makes compliance manageable even for SMEs and ensures packaging design aligns with both regulatory and stakeholder expectations.

Asia-Pacific – which includes some of the world’s largest plastic producers and users – is rapidly adopting plastic policies as well[22]. Many Asian countries have historically faced severe plastic pollution challenges (e.g. marine plastic outflows from China, Southeast Asia, and India have been among the highest). Now we see a wave of new regulations:

- China has implemented a phased plan to restrict single-use plastics. Since 2020, China’s government has issued bans on ultra-thin plastic bags and single-use straws nationwide, aiming to phase out non-degradable bags in major cities by 2025. China also since 2018 banned the import of foreign plastic waste, a policy that reshaped global waste flows and forced many countries to deal with their own plastic scrap. Additionally, China is piloting EPR-like measures in industries such as electronics and automotive, and encouraging plastics recycling investment, though a comprehensive national EPR for packaging is still in development[25].

- India in 2022 updated its Plastic Waste Management Rules to introduce mandatory EPR for plastic packaging[26]. Indian producers, importers, and brand-owners must register and meet annual recycling or recovery targets – for example, ensuring a certain percentage of the plastic they put on the market is collected and recycled each year. If they cannot meet targets directly, they can purchase “plastic credits” from accredited waste processors to make up the shortfall. The rules also mandate the phasing out of certain single-use plastics (India banned items like plastic straws, cutlery, earbuds with plastic sticks, etc. effective July 2022). India’s EPR scheme is notable for allowing a market for surplus recycling certificates, essentially creating a tradeable credit system for plastic waste recovery. This is spurring the growth of organizations that help companies comply by executing collection and recycling on their behalf.

- Japan has long had a Packaging Recycling Law (since 1995) and a culture of sorting waste; consumers pay a fee for recycling packaging and industry consortia handle the processing. South Korea implemented EPR for packaging back in 2003 and has aggressively ramped up recycling requirements (Korea boasts one of the highest plastic recycling rates in Asia at ~45% for packaging, by some estimates). South Korea also uses a deposit-refund system for certain products and has recently required clearer recycling labels and even banned colored PET bottles to improve recyclability[27].

- Southeast Asian countries are moving as well: Vietnam launched EPR for packaging in 2024, requiring producers either take back packaging waste or pay into a government Environmental Protection Fund[28]. Thailand has a roadmap to achieve 100% recyclable plastic by 2027 and is considering EPR mechanisms. Indonesia and Malaysia have strategies to reduce ocean plastic leakage by 70% and are trialing EPR in certain sectors. Australia and New Zealand have been implementing product stewardship and are aiming for all packaging to be recyclable or compostable by 2025 (Australia also has a voluntary pact with industry on recycled content, though recently it’s considering mandatory measures due to slow progress).

Overall, Asia-Pacific’s regulatory trend is toward catching up with or even leapfrogging Western standards: many countries in the region now recognize that solving waste management is crucial and are requiring businesses to take responsibility for packaging end-of-life[29][30]. For multinational companies, this means compliance in Asia is becoming as important as in Europe – which is a notable change from a decade ago when such regulations were sparse in developing markets.

Other regions: In Africa and Latin America, numerous countries have instituted bans or taxes on single-use plastics, especially plastic bags. For example, Kenya famously banned plastic bags in 2017 with strict penalties, achieving a dramatic reduction in bag use. Dozens of African nations now have some form of plastic bag ban or levy. The challenge in many of these countries is enforcement and providing affordable alternatives. Some countries (like South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana) are exploring EPR or already have packaging take-back programs initiated by industry. Latin America has standout cases like Chile, which was the first in the Americas to ban retail plastic bags nationwide (in 2019) and has a new EPR law for packaging; and Colombia, which has EPR for packaging and a tax on plastic bags. While approaches differ, the global regulatory trend is clear: more and more jurisdictions are implementing rules to reduce single-use plastics and make producers financially responsible for waste management. The patchwork of regulations can be challenging for companies to navigate – the lack of alignment between different countries’ rules increases compliance costs and complexity for global brands[31]. This is one reason many large companies advocate for harmonized standards (and are actively participating in the UN treaty discussions to help shape consistent global rules).

To illustrate the regulatory landscape, List below provides a snapshot of key plastic-related policies in major regions:

- Europe

- EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive – Requires all Member States to implement EPR for packaging by 2024[20]; sets recycling targets (50% of plastic packaging by 2025, 55% by 2030).

- Single-Use Plastics Directive (2019) – Bans certain single-use items (straws, cutlery, etc.) and imposes reduction measures.

- Upcoming EU Packaging Regulation – Proposes mandatory reuse targets and recycled content (e.g. 30% recycled plastic in beverage bottles by 2030). Many countries also impose plastic taxes or fees.

- North America

- United States (select states) – No federal law; state-level EPR laws in CA, WA, CO, OR, Maine, Maryland etc. (e.g., California SB54 mandates 25% reduction in single-use plastic packaging by 2032 and 65% recycling rate for plastic packaging[23][24]). Widespread local bans on plastic bags (8 states) and foam food containers.

- Canada – Federal ban on 6 single-use plastic items (2023); provinces implementing EPR for packaging (e.g., Ontario, Québec).

- Asia-Pacific

- China – Phased bans on non-degradable plastic bags and single-use plastics by 2025; strict import ban on plastic waste since 2018.

- India – Plastic Waste Management Rules (2022) enforce EPR for plastic packaging with mandatory recycling/credit obligations[26]; national ban on many single-use items.

- Japan & South Korea – Long-standing EPR programs (Japan’s 1997 Packaging Recycling Act; Korea’s 2003 EPR with deposit schemes)[27].

- Southeast Asia – Vietnam EPR for packaging from 2024[28]; Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia rolling out EPR and various bans.

- Australia/NZ – Target 100% recyclable packaging by 2025; moving from voluntary pledges to possible mandates.

- Other Regions

- Africa – ~34 countries have plastic bag bans or taxes; Kenya, Rwanda among the strictest. The African Union is developing a continental action plan on plastic pollution.

- Latin America – Chile and Peru banned plastic bags; Chile has EPR for packaging; Mexico City banned many disposables. Regional blocs (e.g. MERCOSUR) have non-binding agreements to cut plastic waste.

List Above: Selected regulatory measures addressing plastics across regions. As shown, Europe is leading with comprehensive rules, while North America and Asia are rapidly adopting EPR and bans in a more piecemeal fashion. These regulations create both compliance obligations and market opportunities – for example, increasing demand for recycled plastic (to meet content targets) and for alternative materials. They also signal that the era of “cheap and easy” disposable plastic is coming to an end. For corporate sustainability leaders, staying ahead of these regulations is now a strategic imperative.

Corporate Sustainability Initiatives and Industry Response

Facing public pressure and this tightening policy landscape, companies – particularly consumer packaged goods (CPG) firms and other large plastic users – have begun to fundamentally re-evaluate their relationship with plastics. Many industry leaders now have formal plastic sustainability commitments, often with 2025 or 2030 deadlines, and are investing in solutions to reduce their plastic footprint. In this section, we analyze how companies are responding through voluntary initiatives, innovation, and participation in new systems like plastic credit programs.

Voluntary commitments: Over the past five years, dozens of major global brands (Coca-Cola, Unilever, Nestlé, P&G, PepsiCo, and others) have signed onto initiatives such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, pledging to change how they use plastics. Together, signatory companies represent about 20% of all plastic packaging produced globally[32], indicating significant industry buy-in. Typical corporate goals include: making 100% of packaging recyclable, compostable or reusable by 2025, reducing virgin plastic usage by x%, and increasing recycled content (often aiming for 25–50% average recycled content in packaging by 2025–2030). For example, Unilever committed to halve its virgin plastic by 2025, and Coca-Cola aims to use 50% recycled material in its bottles by 2030. However, progress reports show mixed results. By 2023, participants of the Global Commitment had only reduced their aggregate virgin plastic use by ~3% compared to 2018 (against a target of 18% reduction by 2025)[33][34]. While there was a notable uptick in using recycled content (post-consumer recycled plastic made up about 14% of packaging for these firms in 2023, up from 5% in 2018)[34], key goals like full recyclability of packaging are likely to be missed. In fact, the majority of those companies will not achieve their 2025 targets and some have extended timelines to 2030[35][36]. This reveals the challenges in shifting supply chains quickly – limitations in recycled plastic supply, lack of recycling technology for certain packaging formats, and sometimes cost and performance trade-offs. Nonetheless, the voluntary corporate push has driven important progress: for instance, many brands have eliminated problematic materials (like PVC or expanded polystyrene) from packaging, introduced lightweighting (using less plastic per package), and experimented with refill and reuse models (though reuse remains niche at just ~1% of packaging for leading brands)[37].

Design and innovation: A key focus for companies is redesigning packaging for sustainability. This aligns with the concept of “Design for Recycling and Circularity.” Product and packaging design teams are now considering end-of-life from the start: selecting materials that are recyclable, avoiding multimaterial or dark-colored plastics that hinder recycling, and opting for formats that use less plastic overall. For instance, some beverage companies moved from shrink sleeve labels (which contaminate PET bottle recycling) to easily removable labels; others shifted from rigid plastic to fiber-based packaging for certain applications. There is also growing interest in compostable and bio-based plastics for specific use cases (though these come with their own challenges and are not a panacea for all products). Forward-looking companies realize that future packaging must be designed with both customer experience and post-use recovery in mind – essentially embedding Extended Producer Responsibility principles into the design process[38][39]. This means product teams are starting to ask questions like: How will this packaging be collected and processed after use? and Will it incur high EPR fees? In fact, EPR fees are creating direct financial feedback: since hard-to-recycle packaging now costs more to put on the market (in countries with modulated fees), design teams have a concrete incentive to improve recyclability[21]. Companies are also innovating with refillable and reusable packaging systems – from reusable glass bottle networks to refill stations for cleaning products. Although reuse models are still nascent (and only make up ~1% of packaging for major brands currently[37]), they offer potential long-term disruption to the single-use paradigm.

Another area of innovation is advanced recycling and materials technology. Chemical companies and startups are developing advanced (chemical) recycling processes to break down plastic waste into petrochemical feedstocks that can be used to make new plastics of virgin-like quality. This could potentially handle plastic types that mechanical recycling cannot, such as mixed or contaminated streams. Several large companies (e.g. Eastman, SABIC, ExxonMobil) have announced investments in such technologies, and some chemical recycling plants are coming online. However, the technology is still in early stages, with questions around economic viability, environmental impact, and how to count it in regulations. Still, companies often include advanced recycling in their strategy to achieve high recycled content goals where regular recycled resin is insufficient. On the materials side, firms are researching alternative materials – bioplastics (PLA, PHA, etc.), paper-based composites, edible packaging, algae-based materials, etc. While none of these have yet replaced conventional plastics at scale, niche uses are growing (for example, compostable plastic for food service items in closed settings, or molded fiber replacing some plastic trays).

Extended Producer Responsibility compliance: As described earlier, many companies must now directly manage or fund the recycling of their packaging in various markets. This has led to industry collaborations such as the Plastic Pacts (national-level partnerships of businesses, government and NGOs aiming to hit circular economy targets) and investments in improving waste management infrastructure. Companies are forming or funding Producer Responsibility Organizations to handle their obligations. Some are taking it a step further – for example, consumer goods companies partnering with waste management firms to ensure more of their packaging is collected and recycled (Coca-Cola investing in PET recycling facilities, or Nestlé funding collection programs in Southeast Asia, etc.). By proactively engaging in EPR programs, companies can help shape how fees are used (ideally to improve recycling systems) and potentially get credit for using eco-friendly packaging (as some EPR fee structures allow fee discounts for easily recyclable or reusable packaging).

Importantly, corporates are learning to view EPR not just as a compliance cost but as a catalyst for innovation. By treating regulatory requirements as design parameters, some companies have discovered new opportunities – for instance, reinventing products to eliminate unnecessary plastic can also reduce costs and appeal to eco-conscious consumers. As one guide put it, teams are trying to “turn EPR requirements into product advantages,” using the challenge to spark creativity in materials and formats [40]. This mindset shift can lead to win-wins: less plastic used, lower regulatory fees, and a sustainability marketing edge. In effect, regulation is driving competition on sustainability in the plastics market – a notable change from the past where using more plastic was often the easier path.

Plastic recovery systems : Another emerging component of corporate strategy is the use of Verified Plastic Recovery Units, as championed by organizations like rePurpose Global. The idea is that for every unit, a defined quantity of plastic waste (often measured in kilograms or tons) is extracted from the environment or recycled, above and beyond business-as-usual. For instance, a company that still uses multi-layer plastic sachets (not recyclable in practice) might purchase credits to support the collection of an equivalent amount of plastic waste in polluted areas, thereby taking responsibility for the impact.

Plastic recovery investments inject much-needed funding into waste cleanup and recycling projects, often in developing countries where the money has high impact. They also make a company’s commitments tangible – rather than just promising to reduce plastic, a firm can demonstrate it paid to remove X tons of plastic from the environment. It’s vital that companies treat investments in downstream recovery initiatives as a complement, not a substitute, to reduction efforts[41].

From an investor and consumer standpoint, corporate responsibility on plastics is now a mainstream expectation. Public companies are being asked by investors to disclose plastic footprints and demonstrate risk management (e.g., how are they preparing for potential plastics regulations or reputational damage?). Retailers like Walmart and Amazon have introduced sustainability requirements that include packaging waste criteria for their suppliers. Consumers in many markets show preference for sustainable packaging and some willingness to pay a premium or switch brands over plastic concerns (especially among younger demographics). All these pressures mean that business-as-usual plastic use is increasingly seen as a liability – both in terms of brand trust and future regulatory costs.

In summary, the corporate response in the plastics market can be characterized by a mix of proactive innovation, voluntary pledges, and adaptation to new policies, with an overarching goal of transitioning from a linear to a circular model for plastics. While progress is uneven and challenges remain (particularly with flexible plastics, multi-material packaging, and scaling reuse systems), the direction is clearly set: companies are striving to use less plastic, better plastic (i.e., recycled or recyclable), and to take responsibility for the afterlife of their products. The next section will discuss the outlook and emerging solutions that could shape the future of the plastics market.

Emerging Solutions and Market Outlook

Looking ahead, the plastics market is at a pivotal juncture. The coming decade will likely determine whether we bend the curve of plastic waste and forge a more sustainable, circular economy for plastics, or continue on an unsustainable path. There are several emerging solutions and trends that offer hope, as well as potential headwinds to be mindful of. In this section, we analyze what the future might hold, from alternative materials to economic shifts and the role of continuing innovation.

Scaling up circular economy infrastructure: A critical foundation for change is investment in waste and recycling infrastructure globally. Many countries are now doing this – whether through EPR funds, public investment, or development aid. The market for plastic waste substitutes and circular services is growing. In fact, trade in non-plastic substitutes (like paper products, textiles from natural fibers, etc.) reached $485 billion in 2023, indicating robust growth in industries that can replace some plastic uses[45]. We can expect to see improved collection systems (e.g. more cities implementing separate collection for recyclables, expansion of container deposit schemes for bottles, etc.), and new recycling facilities coming online, including both mechanical and chemical recycling plants. China’s waste import ban sparked many Southeast Asian nations to also limit imports and focus on domestic recycling capacity. Countries like Indonesia and India, with support from alliances and multinational companies, are developing better systems for collecting packaging waste from rural and urban areas (often employing digital tools to connect waste pickers or incentivize returns). As infrastructure expands, the supply of recycled material should increase, helping to alleviate the current shortage of high-quality recycled plastics. This, in turn, can help companies reach recycled content goals and potentially drive down the cost gap between recycled and virgin plastic. A key metric to watch will be global recycling rates – the goal is to push that global average from ~10% closer to 30% or more in the next 10-15 years. Some regions (EU, etc.) will likely exceed 50% recycling of plastics with the combination of EPR, deposits, and improved technology, showcasing what might be possible elsewhere in time.

Innovation in materials: We anticipate continued innovation in polymer science and alternative materials aimed at reducing environmental impact. One avenue is bioplastics – plastics made from renewable biological sources (like corn, sugarcane, or even captured carbon emissions) rather than fossil fuels. Some bioplastics are also designed to be biodegradable or compostable under the right conditions. The bioplastics market is growing (albeit from a very small base, currently <1% of total plastics). These materials could play a role in specific applications (for example, compostable packaging for food service that can be industrially composted with food waste, or bio-based “drop-in” plastics like bio-PET that are chemically identical to normal PET but with lower carbon footprint). However, challenges such as competition with food crops, required composting infrastructure, and ensuring they don’t contaminate recycling streams will need addressing.

Another material trend is paper and fiber replacing plastic for certain single-use items. We have seen a surge in paper-based solutions (like molded fiber plates, paper straws, fiber-based flexible packaging with thin coatings, etc.) as companies seek to eliminate hard-to-recycle plastics. These alternatives have to balance functionality (barrier properties, strength) with sustainability (sourcing from responsibly managed forests, recyclability). Similarly, reusable materials like steel, glass, or durable polymers are being reconsidered for packaging that can circulate many times (e.g., stainless steel kegs or containers for refill programs).

In the long run, rethinking product delivery models could drastically reduce plastic demand. For example, if more products move to concentrated refills, dispensing systems, or package-free retail (like bulk stores or dissolvable pods), the need for single-use packaging diminishes. Some companies are already exploring selling products as a service or via refill stations – these models are small today but could grow with consumer acceptance and clever design (for instance, shampoos in solid bar form instead of bottled liquid, etc., eliminate plastic containers altogether).

Economic instruments and market shifts: We should also consider economic drivers. As regulations ramp up, the cost of using virgin plastic is likely to rise. This could be through direct taxes (some countries have considered taxes on virgin resin or on plastic packaging that is non-recyclable), higher EPR fees, or carbon pricing that factors in the fossil fuel usage of plastics. At the same time, recycled plastics could become relatively cheaper if economies of scale improve and if policy favors them (e.g., tax credits for using recycled content). Already, we saw how trade policies historically made virgin plastic artificially cheap (low tariffs on plastic vs higher on substitutes)[18]. Correcting these distortions – for example, lowering barriers for import/export of recycled materials or components thereof – could bolster a more circular market. If oil prices fluctuate or if global climate policies tighten (making fossil extraction pricier), virgin plastic costs will be affected since naphtha (oil) and ethane (gas) are primary feedstocks. Some petrochemical companies might face stranded assets in the future if demand for virgin plastics slows due to environmental limits or widespread recycled replacement.

On the flip side, demand for plastic is still expected to grow in certain sectors (healthcare, construction in developing countries, etc.), so the market for “sustainable plastics” – meaning those that are recycled, lower-carbon, or better managed – is where growth could be redirected. The concept of a “plastic circular economy” might drive new business models: for instance, companies could take back their own packaging (closing the loop), or specialized firms will emerge that offer packaging-as-a-service, handling reverse logistics and reuse for multiple client companies. The opportunity in building a circular plastics sector has been valued in the tens of billions of dollars globally.

Consumer and cultural change: Another factor to the outlook is the role of consumers and culture. We are witnessing shifting attitudes – what was once normal (say, automatically getting a plastic bag or straw) is increasingly seen as undesirable. In many places, consumers now bring their own bags or prefer brands with less plastic. Social media campaigns exposing excessive plastic packaging or pollution have dented reputations. Consumer pressure will likely continue to push brands toward greener packaging solutions. Younger consumers especially are highly engaged on sustainability; companies targetting Gen Z and millennials often tout their minimal packaging or use of ocean plastic material in products, etc., as selling points. If a tipping point is reached where sustainable packaging becomes a baseline expectation (like organic or fair-trade did in other domains), laggards in the market will lose out. There is also an education component – making sure consumers know how to properly dispose of or recycle packaging is crucial. Many companies and governments are investing in consumer education (standardized recycling labels, awareness campaigns) so that good design isn’t wasted by improper disposal at end of life.

Challenges and unknowns: Despite positive trends, challenges abound. Flexible plastics (films, sachets, wraps) are a huge portion of packaging, especially in Asia and for low-cost consumer goods, yet they are the hardest to collect and recycle. Innovations like soluble or recyclable mono-material pouches are emerging, but not fast enough to replace multi-layer films in all cases. Without breakthroughs, those flexibles could continue to leak into the environment. Packaging for food and medical safety also poses issues – sometimes plastic is genuinely the best material (lightweight, hygienic) and finding safe, equally efficient alternatives or reuse systems will take time. Additionally, legacy infrastructure and investments can slow change: companies that have billions invested in plastic packaging lines or supply contracts can’t overhaul them overnight. They need to balance the pace of change with business realities, which is why many set 2025 or 2030 goals to allow gradual transitions.

Moreover, the effectiveness of policies like EPR will depend on execution. If EPR fees are too low or enforcement weak, it may not drive much change. Conversely, if poorly designed, it could lead to unintended consequences or simply higher costs passed to consumers without environmental benefit. The impending global treaty, if agreed, will be historic – but then comes the hard part of implementation and ratcheting up ambition over time.

Another wildcard is technological breakthroughs. For instance, if someone commercializes an enzyme or chemical process that can cheaply break down any plastic to basic molecules, that could revolutionize recycling (a few startups and research labs are working on enzymatic recycling for PET, with early successes in breaking it down to monomers for re-polymerization). Or consider if new materials (like PHA biopolymer, which is truly biodegradable in nature) could be scaled cheaply – that might replace a chunk of single-use plastics especially in marine applications like fishing gear or agricultural films. These breakthroughs could accelerate the sustainability shift beyond current projections.

Market outlook: On balance, the plastics market of the future will likely be shaped by stronger controls and a move towards circularity. One might say we are entering the “Plastic Transition,” akin to the energy transition – an era where business models adjust to decouple plastics from environmental harm. In concrete terms, by 2030 we can expect:

- Lower growth in virgin plastic demand in advanced economies, possibly even stagnation or decline in certain single-use segments, offset by growth in recycled and bio-based plastics. (Global demand will still grow but slower if policies work.)

- Much higher recycling rates in leading markets (e.g. EU aiming for 55% of packaging, some countries may hit that or more), and moderate improvements globally as infrastructure spreads.

- Increased costs for wasteful packaging – companies using unrecyclable plastics will be paying more (through EPR fees, carbon costs, or taxes), making virgin plastic less of an “externality-free” cheap resource.

- Innovation-driven market entrants – for example, more startups offering plastic-free products, new materials, or refill delivery systems capturing market share from incumbents who are too slow to change.

- Global treaty influence – if a treaty is finalized by 2025, by 2030 countries will be implementing its provisions, which might include caps on virgin plastic production or requirements to use recycled content globally. This could really bend the curve of the plastics market in the later 2020s.

From an investor perspective, companies that adapt and offer solutions (recyclers, makers of sustainable materials, etc.) stand to gain, whereas those anchored to the status quo virgin plastic model face regulatory, reputational, and possibly demand risks. Already, we see petrochemical giants diversifying into recycling (some acquiring recycling companies or launching their own) and at least rhetorically supporting circular economy principles.

For corporate sustainability and CPG leaders reading this analysis, a few key takeaways emerge about the market trajectory: - Regulation will only tighten: preparing early (embedding EPR into design, phasing out problematic plastics ahead of bans) turns a compliance burden into a competitive edge[38][39]. - Transparency and measurement of plastic footprints is now essential. What gets measured gets managed – companies need robust data on how much and what type of plastic they use, where it ends up, and what alternatives can be employed. - Diversification and flexibility in materials will be important. Relying on one packaging material (like conventional plastic) is risky; the market is moving to a mix – recycled resins, bioplastics, paper, aluminum, glass, etc., each in the applications where they make most sense. The winners will be those who optimize across this spectrum while minimizing environmental impact. - Collaboration is key. Engage in pre-competitive collaborations, whether through industry coalitions or public-private partnerships, to solve common challenges (like building recycling capacity or establishing collection in emerging markets). Sharing knowledge and co-investing in solutions can reduce costs and speed up progress. - Consumer communication and engagement: Bring customers along by innovating in ways that enhance user experience (e.g. easy-to-recycle packaging that is still attractive, or convenient refill options). Educate consumers on how to return or recycle products properly. Brands that empower consumers to participate in waste reduction can build loyalty and brand value.

Conclusion

The plastics market is undergoing a profound transformation as sustainability considerations move from the periphery to the core. What was once an almost singular focus on growth and convenience is now tempered by the realities of environmental limits and public expectations. In this analysis, we’ve seen that plastics are at a crossroads: on one hand, production and consumption remain on an upward path globally, but on the other, there is unprecedented momentum to change course – through policy, corporate action, and innovation.

For consumer goods companies and corporate sustainability leaders, the writing on the wall is clear. Embracing a circular economy for plastics is not just about doing what’s right for the planet; increasingly, it’s about business resilience and staying competitive. Regulations like EPR are making sustainability a license to operate. Companies that proactively reduce reliance on virgin plastic, design for recyclability, and invest in waste reduction will be better positioned in a future where plastic waste is constrained and penalized. Those that delay may find themselves facing higher costs, supply chain disruptions (e.g. shortages of recycled material or sudden bans on certain packaging), and loss of market share to more agile, eco-friendly competitors.

However, the transition need not be viewed in purely challenging terms – it is also a time of opportunity and innovation. Rethinking plastics opens the door to creative solutions that can also improve customer experience or operational efficiency. For example, developing refillable packaging systems could foster new customer touchpoints and loyalty. Using recycled materials can reduce dependence on volatile petrochemical markets. Solving the plastic problem can yield goodwill that translates into brand value. In essence, sustainability can drive the next wave of product and packaging innovation, much like digital technology did in prior decades.

It is also worth noting that solving plastic pollution offers broader societal benefits – cleaner cities and oceans, green jobs in recycling and remanufacturing, reduced greenhouse emissions, and improved public health. Companies that contribute to these solutions can strengthen their social license to operate and relationships with governments and communities. Many firms have started to frame their plastic initiatives as part of their ESG (environmental, social, governance) performance, which investors are scrutinizing. As investor focus on climate and sustainability grows, plastics management is now frequently part of ESG metrics and indices (for example, some ESG ratings consider a company’s packaging footprint and actions to mitigate it).

In conclusion, the plastics market of tomorrow will likely be defined by circularity, accountability, and innovation. Achieving this will be a shared journey – requiring coordination between policymakers, businesses, and consumers. Encouragingly, we see the seeds of this future in the trends discussed: governments aligning on a global treaty, industries collaborating on recycling breakthroughs, and consumers willing to change habits to #BeatPlasticPollution.

From a thought leadership perspective, one can envision a scenario a decade or two from now where the plastics economy has been fundamentally reinvented: most packaging is recycled or reused, new plastics are bio-based or carbon-neutral, and leakage to the environment has been drastically curtailed. Getting there will take relentless effort and probably some course-correcting along the way, but each step – whether it’s a new EPR law, a company eliminating unnecessary plastics, or a community cleanup funded by Verified Plastic Recovery projects – is contributing to that systemic shift.

[1] [7] [18] [19] [31] [45] Global Trade Update (August 2025): Mobilising trade to curb plastic pollution | UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

[2] [3] [4] [8] [13] [15] Everything you need to know about plastic pollution

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/everything-you-need-know-about-plastic-pollution

[5] [6] [12] [44] The Plastic Waste Management Framework | AEPW

https://www.endplasticwaste.org/insights/reports/plastic-waste-management-framework

https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/plastics.html

[11] [14] [16] [17] World Environment Day, June 5

https://forourclimate.org/insights/57

[20] [21] Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for Packaging: Country-by-Country Comparison | Net Zero Compare

[22] [38] [39] [40] Embedding EPR Principles into Packaging Design_ A Guide for Product Teams.pdf

file://file-8qLeGbDZRpjpzqg8kpvYkX

[23] California - Circular Action Alliance

https://circularactionalliance.org/california

[24] How to: Navigate California's new plastic pollution mandate

[25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] EPR in Asia Pacific - What Retailers and Manufacturers Need to Know

https://deutsche-recycling.com/blog/epr-in-asia-pacific/

[32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] EMF global commitment signatories make progress on recycled content, lag on plastic reduction | Packaging Dive

[41] [42] [43] Verified Plastic Recovery Units Explained_ How They Fit Into a Corporate Sustainability Strategy.pdf

file://file-MNnsW1LY8wiut77TaMMEKJ

.jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)